"As locating information has become easier, evaluating information has become more difficult"

-Brookbank and Christenberry, 2019, p. 55

There is a great deal of information available from several sources both across the open web and within library databases. Just because the information is available does not mean that it is factual or correct. It is often recommended that you search within library databases for sources, as they are "more precise and effective than internet search engines" (Brookbank & Christenberry, 2019, p. 55), but you must still evaluate the information that you locate within them.

![]()

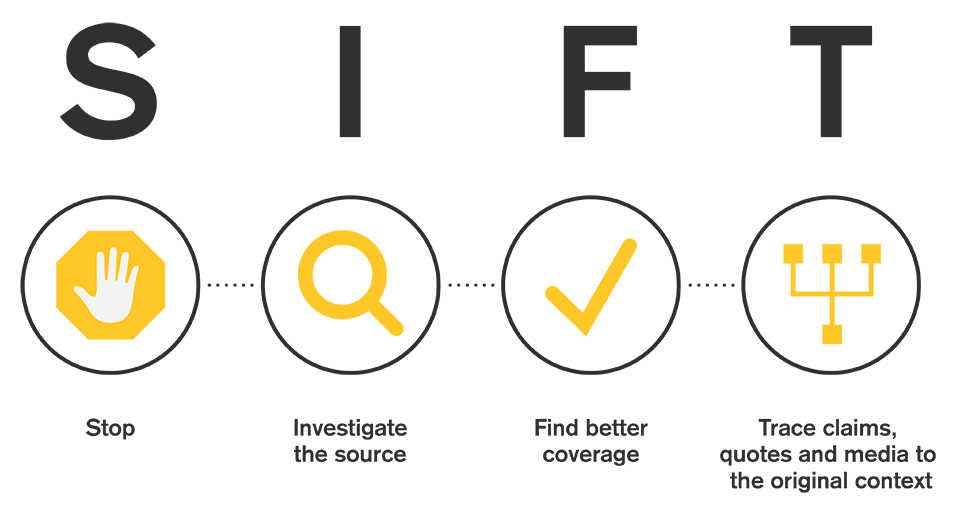

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging!

![]()

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating.

![]()

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there.

![]()

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented.

"As locating information has become easier, evaluating information has become more difficult" (Brookbank and Christenberry, 2019, p. 55).

There is a great deal of information available from several sources both across the open web and within library databases. Just because the information is available does not mean that it is factual or correct. It is often recommended that you search within library databases for sources, as they are "more precise and effective than internet search engines" (Brookbank & Christenberry, 2019, p. 55), but you must still evaluate the information that you locate within them.

One must take the time to properly evaluate and think critically about what it is that they are looking at. There are many methods, such as the CRAP Test, to help with evaluating information, but these can cause people to only take information at face value. Instead of simply making sure an article or source checks a few boxes, look at the article or source and ask yourself some questions, think critically about what you are looking at (Knott, n.d.). This may take a bit longer, however, it will provide a greater return on the investment of your research time. It will also help you to become a critical reader and a critical writer. According to Knott (n.d.), "to read critically is to make judgements about how a text is argued." This technique enhances your research process because it aids you in getting to the core of the material you are using. The two main keys to becoming a good critical reader are "don't read looking only or primarily for information," and "do read looking for ways of thinking about the subject matter" (Knott, n.d.).

Questions to ask upon evaluating resources:

Instead of looking at the source and wondering what information you can get out of it, ask questions such as “How is this text argued? How is the evidence (the facts, examples, etc.) used and interpreted? How does the text reach its conclusions?"

Asking questions should lead to more questions, this is a good thing. You should always dig deeper. Doing so will make you a better researcher, and it will enable you to find, use, and share credible sources more easily.

Suggested Resources

References

Brookbank, E., & Christenberry, H.F. (2019). MLA guide to undergraduate research in literature. Modern Language Association of America.

Butler, W.D., Sargent, A., & Smith, K. (2021). The SIFT method. In Introduction to college research. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.pub/introtocollegeresearch/chapter/the-sift-method/

Knott, D. (n.d.). Critical reading towards critical writing. Writing Advice, University of Toronto,

https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/critical-reading/

Northern Essex Community College Library. (3 December 2021). Evaluating Sources. ENG 102: English Composition II.

https://necc.mass.libguides.com/ENG102/evaluating

Umpqua Community College Library, 1140 Umpqua College Rd., Roseburg, OR 97470, 541-440-4640

Except where otherwise noted, content in these research guides is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.